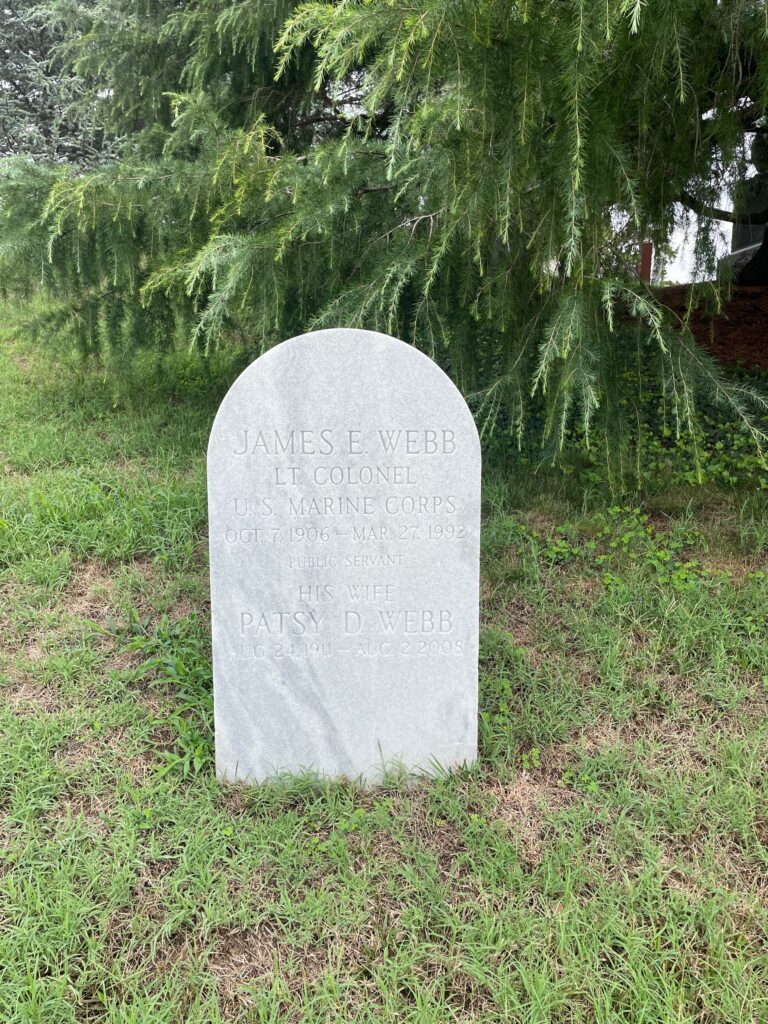

This is the grave of James E. Webb.

Born in 1906 in Tally Ho, North Carolina (what a name!), Webb grew up pretty well off. His father was county superintendent of schools, segregated of course. He went to the University of North Carolina, graduating in 1928. He then joined the Marines, which was not a common move in 1930, when he signed up. There was hardly any room to move up, this was the isolationist period of America, so the military didn’t have much funding. But it did need pilots and that was Webb’s job. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and was on active duty until 1932.

Upon leaving the Marines, Webb decided on politics as his future. He became an aide to a congressman named Edward Pou, who was hugely powerful in his day and had done a lot of work to overturn the Red Scare after World War I. Pou was at the very end of his time, though still chair of Rules Committee. The Roosevelt administration needed New Deal legislation to get through Congress and Pou made that happen. Given Pou’s age, young men like Webb played important roles in keeping all this together. At the same time, Webb enrolled in George Washington Law and got his degree in 1936, being admitted to the DC bar soon after. In those last couple years, he was working privately for Oliver Gardner, another today unknown but then powerful Democrat, who was the former governor of North Carolina and who had a prominent DC law firm.

In 1936, Webb was hired by a company called Sperry Gyroscope. They did all sorts of electronic equipment. The firm expanded rapidly during World War II. Webb rose rapidly and became VP by the time he rejoined the Marines in 1944. This meant a huge expansion in radar systems, setting the company up to be a major player in the military-industrial complex then forming. He actually wanted to join the Marines in 1941, but he was declared too important to developing weapons to fight, which actually seems like a very reasonable position for the government to take. But he kept persisting and so he was let back in as a captain and soon was a major, commanding a Marine air wing and finishing his time as lieutenant colonel. He was then put in charge of planning the radar program for the upcoming invasion of Japan, but of course that didn’t happen.

Perhaps Webb wanted a career change anyway. Instead of going back to Sperry after the war, he went back to his old mentor Gardner, who was then Undersecretary of the Treasury. He got a job there and was very shortly recommended to Harry Truman as a good candidate to lead Bureau of the Budget in the president’s office, which was mostly in charge of dealing with budget issues in relationship to Congress. He did well enough at this that in 1949, Truman named him an undersecretary of state. He was a good organizational man and Dean Acheson tasked him in reorganizing State. He proved a pretty influential insider. He helped convince Truman to support Paul Nitze’s NSC-68 memo to build up NATO, which was opposed by Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson, among other more powerful figures. Webb was also a knife-wielding insider. He soon had his revenge on Johnson, using his congressional friends to pressure Truman to dump him and replace him with George Marshall.

But Webb found himself outmaneuvered, mostly by Nitze, and decided to leave government in 1952. He returned to the private sector and spent the next nine years mostly in defense work, but occasionally doing bits of government work too. But in 1961, John F. Kennedy named Webb the head of NASA, a huge undertaking as Kennedy also pledged to get Americans to the moon. He would stay in that position until 1968, making him the second longest NASA head to the present (Charles Bolden was in there for the entirety of the Obama administration). It’s almost impossible to overstate Webb’s importance here. NASA was still a new agency. It was decentralized. Its mission wasn’t that clear. Webb transformed all of this. Sure, he’d push the Apollo program, but he also made sure to work Congress hard for funding for the interplanetary missions in the Mariner and Pioneer programs. He centralized operations at what would later be known as the Johnson Space Center in Houston. He was so well-connected and had the full backing of both Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson and so he worked Congress lobbying for the agency very hard and quite successfully.

There’s another key aspect to Webb’s leadership. Like LBJ, Webb was a southern white boy who turned his back on white supremacy as an adult. He actively supported the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and determined to make NASA a leader in hiring minorities. Once Webb and (of all goddamn people) Wernher von Braun confronted George Wallace in public over this, I think over hiring black workers at the NASA facility in Huntsville, Alabama. Under the Eisenhower administration, almost no black workers were hired but by 1968, NASA was a leader in all the government for hiring black workers and that’s especially true compared to the other highly specialized scientific agencies.

Webb also took personal responsibility when Apollo 1 blew up and did all the PR work to save the agency and convince Americans that NASA was safe. He led a very public safety investigation and made himself point person, much to the relief of LBJ, who did not need more headaches in 1967. He also started writing a book about administration. I doubt it’s a very exciting read, but 1969’s Space Age Management: The Large-Scale Approach is in some ways a classic of Great Society liberalism. It took the managerial approach, placed himself as an ideal leader who could be emulated (anyone who writes about this stuff basically sees themselves as the ideal) and stated that the enormity of running NASA was a good model. But unlike basically all managerial books, he didn’t mean it was a good model to run a corporation. He meant that people fighting and other social problems could work for government agencies with as much money and power as NASA and fix those problems through management. Again, Great Society liberalism in a nutshell. Maybe a bit of a dream, but don’t we all wish this was how things had worked since 1969?

Anyway, Webb resigned when Richard Nixon won the presidency, he became a regent of the Smithsonian, served on tons of big boards for companies and non-profits, did the rich and powerful old person thing. The Webb telescope was later named for him. That became somewhat controversial in 2021 when a Scientific American article said it should be renamed because Webb didn’t fight the expulsion of homosexuals from the space program in the 50s. But there’s no evidence Webb had anything to do with those decisions and the whole thing seems pretty dumb and overwrought to me. It’s not a bad way of thinking about changes in liberalism–from the belief that we can come together and pick everyone up through the managerial state to pure identity politics that is more about symbolism than effective action. Now, if he was Robert E. Lee or something, sure, or, like, had actually played a role in these firings, but this was taking the renaming craze a bit far.

Webb died in 1992. He was 85 years old.

James E. Webb is buried on the confiscated grounds of the traitor Lee, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.

If you would like this series to visit other heads of NASA, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. T. Keith Glennan is in Manns Choice, Pennsylvania and Thomas O. Paine is in Santa Barbara, California. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.

The post Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 2,094 appeared first on Lawyers, Guns & Money.